Reactions

Searching for meaning

Searching for reason

Searching for something, anything

To believe in.

It sat in the corner of the tiny cage. Apparently the other mice had gotten hungry while we were out getting them food. There was a gaping hole in the stomach of a mouse. Exposed organs bubbling out of the body, fragments of white-tan bone broken and sharpened with the marks of starving teeth, and puddles of drying, rotting blood were all that was now left of this mangled creature. His once perfect white fur was now stained with reddish brown blotches of crusted over blood. The edges of his skin – just where his white fur came in contact with the crusty redness – took on the form of a black shell that was being cracked open while the chick is still alive, and nothing but red poured out. His body, ravaged and draping pieces of red and white cloth in the form of severed slivers of skin, no longer felt the pain of life. His body, with eyes staring into the void of the mysterious unknown realms of mortality, lied silent and perfectly peaceful, free from all the other mice. His eyes were still; an eerie stillness that gazed into nothingness.

Searching for reason

Searching for something, anything

To believe in.

It sat in the corner of the tiny cage. Apparently the other mice had gotten hungry while we were out getting them food. There was a gaping hole in the stomach of a mouse. Exposed organs bubbling out of the body, fragments of white-tan bone broken and sharpened with the marks of starving teeth, and puddles of drying, rotting blood were all that was now left of this mangled creature. His once perfect white fur was now stained with reddish brown blotches of crusted over blood. The edges of his skin – just where his white fur came in contact with the crusty redness – took on the form of a black shell that was being cracked open while the chick is still alive, and nothing but red poured out. His body, ravaged and draping pieces of red and white cloth in the form of severed slivers of skin, no longer felt the pain of life. His body, with eyes staring into the void of the mysterious unknown realms of mortality, lied silent and perfectly peaceful, free from all the other mice. His eyes were still; an eerie stillness that gazed into nothingness.

The entire room filled with a choking stench of rotting flesh. There was a sour, moldy, peppery odor that clouded the air. I can still remember how it stabbed the back of my throat like tiny nails of nausea driving into my adams apple. I could hardly swallow which made breathing even harder. My eyes began to water as I gagged on the foul, despicable smell of decaying life. But the mouse lying there cannot smell the suffocating stench of his own squalor. No, he is not scampering around helplessly, aimlessly. He is just peaceful. Perfectly peaceful.

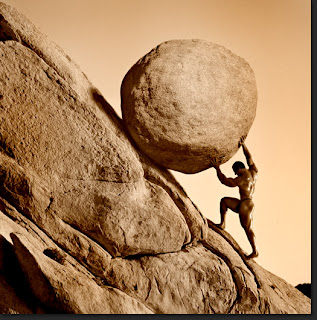

The other mice ran around, climbed on top of each other, picked at pieces of cardboard, and kept jumping to the top of the cage where they would hang on to the iron gate only momentarily before falling back down and trying again. Three mice in particular caught my eye. The first one was one of the mice that repeatedly jumped to the top of the cage, where he would wrap his tiny claws around the metal gating for a minute before falling back down to the bottom. The cage was about one foot tall, one foot wide, and two feet long. It was plastic and covered by a thin iron fencing at the top. It seemed that this mouse believed he could somehow defy gravity and push the iron gate upwards as he was falling down. Poor stupid mouse; he couldn’t even recognize his own imprisonment. He just kept jumping and falling, jumping and falling. What was the point of it all, I wondered. Maybe this somehow gives meaning to the mouse. Maybe, by relentlessly striving for something so far beyond his reach, he has something to hope for, and his mere hope is enough to make him want to continue his life.

The second mouse that caught my eye was one that had blotches of blood streaking down both sides of his face. It looked as if he smeared war paint on his face before jumping in with the rest of the violent mob to feed on our victim. He moved in unison with all the other mice in one great amoeba of mindlessness. The formation, consisting of all of them save the dead one, Sisyphus, and the third one which I have not yet explained, rubbed up alongside each other and huddled in with each other desperately. Every now and again as the mob passed by the silent carcass, the war-painted mouse would jam his nose inside the red pudding and satisfy his temporary desire. After having his quick treat of raspberry tapioca, he would quickly rejoin his friends and return to the herd and its circles of absurdity.

The final mouse that caught my eye seemed to find dissatisfaction with the restlessness of the other mice. He sat in one corner of the cage nibbling on tiny pieces of cardboard. He would take the paper towel roll and grab it with his little bird-like hands and drive into the cardboard incessantly like a squirrel spasmodically nibbling nuts. He just sat there. He was adorable. So seemingly content with what was given to him; if not content, somehow resolved to live contently in a cage. He was just chewing on tiny pieces of cardboard, using what was given to him and making the best out of it. As the other mice ran near him, bumping into him and crawling on top of him he just sat there and accepted the arrogance of the amoeba.

The room was silent save the clicking and tapping of the little bird-like mice claws scampering around the plastic box. I stood in complete awe as I watched scenes of human society be played out in front of me. My roommate then opened the top of the cage and grabbed the dead mouse. As he picked him up, the mouse’s body dangled flaccidly while still pushing out random bubbles of blood like a passed volcano still erupting tiny pools of lava on the scorched mountainside. He wrapped him in a blue recycling bag, tied it up, and took it outside to the dumpster. Poor mouse didn’t even get a proper burial. But then again, what’s the point? None really.

After he removed the dead mouse, I re-opened the cage to give them some food. We had fruits, vegetables, bread, and uncooked pasta. As I crumbled it into their cage, they flocked to it like a stampede, driving claws and teeth into each other in a scurry to fulfill themselves. After feeding the herd, I placed a piece of bread in front of my little buddha, which he greatly appreciated. But the others never seemed to be satisfied. They attacked each other and viciously tore into the food, eating and storing as much for themselves as they could. I thought it was ironic that my offering of food led them to violence. I came to diminish the need for violence by giving them what they initially killed for, and now they seemed as if they wanted to kill each other even more. I couldn’t tell if it was the greediness of the mice or if it was truly a need that they were seeking to fulfill.

But then I looked again at the mouse in the corner. He still just focused on what was in front of him, neglecting to pay any attention to the violently vicious voraciousness of the others. He took his bread and ate it, all alone.

I reached into the cage and grabbed the adorable little mouse and as I grabbed him he curled into a tiny ball in the palm of my hands. Maybe my body gave him a warmth he could not find inside the cage. Maybe he was just scared. Whatever the case, I took him downstairs and went outside. I walked across a field of tall grass towards an abandoned house. The house was burnt long ago and now sat there purposeless as some piece of historical landmark. I sought to make a purpose out of it. I cracked open the door and released my friend just inside the door. As I opened my hand, he darted off my palm into the darkness ahead of him, thinking he had finally attained freedom – if he only knew. My friend, we are never free. Freedom from the herd is all we can achieve while we are here, and that is all I could give him. After doing this I headed back up to the room that still reeked of death, took my little Sisyphus out of the cage, and brought him across the street to the empty house. Maybe now that rock won’t feel so heavy.